I felt that Los Angeles didn’t have anything like this and there should be something that people would look at with a little different view…I felt if we could get some sense of bigness of spirit, it would be exciting.

– Millard Sheets, 1977

I felt that Los Angeles didn’t have anything like this and there should be something that people would look at with a little different view…I felt if we could get some sense of bigness of spirit, it would be exciting.

– Millard Sheets, 1977

In pursuing the project, Millard Sheets, a non-Mason cultural enthusiast, questioned why the Masons required such a big temple or “cathedral.” The artist, avid watercolorist, educator, and successful designer, was tackling the design strategies as communications and symbols meant to connect the increasingly obsolete Masonry with the changing world. Referring to the temple many times as a city, Sheets, like any successful architect, listened and inquired before envisaging any building form, yet even he was surprised by the tremendous number of things and functions that the Masons required for this space.

Original Scottish Rite Masonic Temple lobby by Millard Sheets

The building was obviously well built, and the integral pride and spirit of Masonry symbolized and celebrated. One could not imagine a better building type to convert into an art space—all the high-ceiling rooms, wide-span structures, and extensive wall spaces with few windows—but the sense of closed exclusivity and esoteric social identity could potentially send it towards yet another isolated art bunker. We wanted to combat this perception, and, despite the building’s solid presence, embrace Los Angeles in its own way. For Angelenos and beyond, I think, this history is fascinating—the juxtaposition and conjunction between the bones, body, and the DNA’s of the historic Masonic temple together with the strategic interventions and contemporary acupuncture throughout the building could present a new life of dynamic and mystifying presence.

From the get-go the Foundation and wHY planned to keep the exterior integrity of the building as much as we could, restoring the grand mosaic on the east wall, which depicts the builders of the temple from the days of Jerusalem to Babylon to London and finally here in California, and assuring that all eight of the vandalized larger-than-life travertine sculptures of key Masonic figures from King Solomon to George Washington will still greet visitors along Wilshire Boulevard. Yet we also believe that for this building to truly serve contemporary art and its communities, the overall spaces required dynamic and dramatic transformation. Instantly my inspiration for the transition was an art playground—a place to experience and to explore, an innovative project space where collecting meets experimenting, and thus flexibility.

Lodge Gallery 1.

Photo courtesy wHY © Yoshihiro Makino.

Flexibility has widely become the keyword for twenty-first-century museums as boundaries surrounding exhibition, art, and institution are constantly being pushed and even erased. I like to take a position on flexibility with an attitude—open, confident spaces with qualities and characters need to exist before any flex happens in them. The renovated building provides enough distinction for the experiences to be diverse and fun, while leaving the individual spaces open to be freely used by artists, curators, or the public.

Today we have more and more art, but fewer unique places to see it or and make it. Now, the often-cited accusation that Los Angeles is ambivalent about embracing its history has found the best site to link the past and present. History will live in a different way, with the raw spirit of experimentation left to the artists. Somehow, it seems this kind of place should already have existed. Well, Sheets might have turned out to be right, Los Angeles didn’t have anything like this—until now.

– Kulapat Yantrasast, Principal, wHY

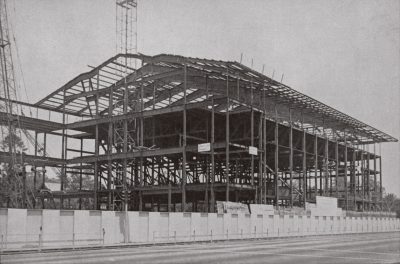

Construction of Scottish Rite Masonic Temple, 1960